Sequellae of stroke - Brainfog, Non-restorative sleep, Executive function deficits, Sensory flooding

Issues that were not recognized during my hospitalization & early rehabilitative efforts, and only identified some 2 years out, included complex cognitive deficits. These are difficult to sort out, and perhaps are interwoven & needn’t be considered separately. The knee bone is connected to the amygdala. These have fallen into the realm of self-discovery and DIY management; in retrospect, I find it rather outrageous that these weren’t anticipated and addressed early in my medical care following stroke. These include:

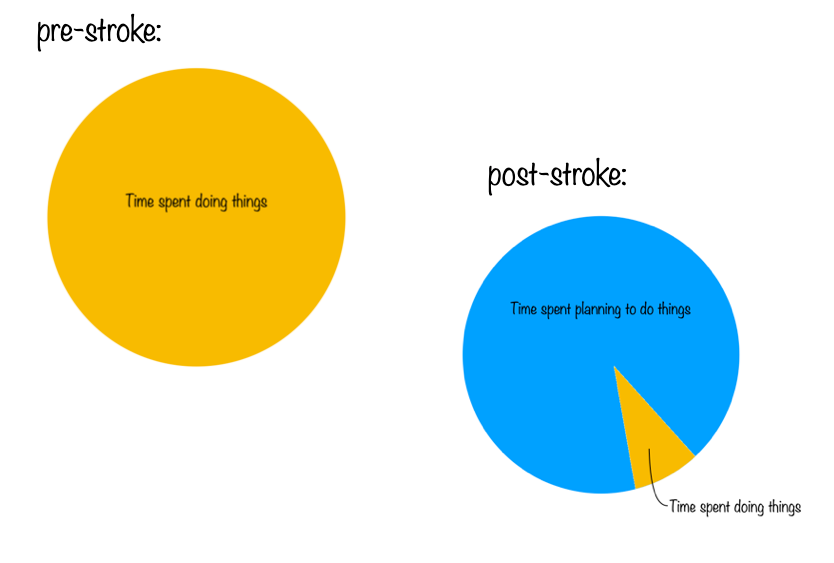

Executive function deficits - particularly difficulties in organization & planning, and in switching attention. I used to think I could “multitask” - which really represents the apparently seamless switching of attention rapidly between competing tasks. Even the more intentional switching of attention between tasks is difficult. The basal ganglia, where my stroke was focused, play an essential role in behavioral switching. On resuming my online teaching, as soon as I was able to navigate the stairway into my home’s basement office, I was able to do the research required, and assemble teaching materials from this, but suffered from my inability to turn attention to the far less pleasant tasks of managing the financial aspects of my business. Planning tasks that required juggling multiple variables proved difficult; functions that previously seemed “intuitive,” not appearing to require conscious attention. This was formally identified in testing in my intake evaluation for a brain injury rehab program my wife & I sought out on our own about 2 years out from my stroke, which offered occupational and speech/language therapy services to assist me in developing strategies for task management. I’ve really struggled with this, & still do, as task management had always seemed rather instinctual for me; as with many of my stroke deficits, this represented a loss of spontaneity & the naturalness of life.

Memory - I was once gifted with eidetic (photographic) memory; I was able to get through college, graduate school, and medical school with no intentional study; I could page through Harrison’s Principals of Internal Medicine or Robbins Pathology, spending less than a minute per page, “absorbing” the content, even later being able to “read” these from my internalized image, and retain this for over 35 years. While my colleagues were struggling with mnemonic devices like “on old Olympus’ Towering Tops,…,” I could visualize the labelled cranial nerves with their assigned functions on an image of the brain in accurate anatomical detail, and could recall the content of lectures attended while knitting, rather than taking notes. My best friend, who seemed to spend every waking moment studying & re-writing his notes and re-listening to recordings of lectures when driving, was terrified I’d flunk out. In my first year of medical school, the department of pathology administered an examination intended to fail the entire class to humiliate us; I scored a 95%, & challenged the 5 questions scored incorrect, referencing the entries in our text (the massive Robbins Pathology), with page & paragraph references recalled from memory, to defend my answers. This gift was cultivated by a speech therapist I was assigned in early grade school to whom I’m forever grateful. But having become accustomed to this gift and accepting it as my norm, on its loss post stroke I’ve had to learn intentional strategies to cultivate working memory. Lately, nearly 11 years out, I’ve had some small glimpses of its partial return; I do the New York Times word games daily to exercise the little grey cells, and have started to “see” these internally after taking a rest from my initial attempts, solving the puzzles in my mind’s eye, this beginning in my dream life and extending to waking experience. Overall, I describe my brain as much like a wheel of Emmenthaler; mostly sharp, but full of some rather large holes. The details of some chunks of my life prior to stroke are missing altogether, despite others being crisp. Formal neuropsychiatric evaluation rated my long- & short-term memory “high normal for age,” which sounds good, but it’s a huge decline from my pre-stroke status. Once again, the need to exercise intentional strategies to cultivate working memory represent a loss of the natural spontaneity of life.

Sensory flooding/overload is a perplexing phenomenon that took me some time to understand; basically, the world at large is overwhelming & exhausting, and it’s frequently necessary for me to isolate for comfort & recovery. A friend with a history of traumatic brain injury introduced me to Claudia Osborn’s book Over My Head, which chronicles a physician’s own experience with closed head trauma, describing the phenomenon of flooding in detail. Basically, it represents an inability to selectively direct attention or filter sensory input; a conversation involving 2 others or more invariably involves at least 3 conversations, and I cannot selectively attend to the one or two that involve me or to sort these out; and adding the presence of a dog or birdsong outside the window or food if the conversation is over a meal becomes overwhelmingly confusing. Riding in a car presents peripheral visual stimulation that is disorienting & exhausting. Grocery stores are particularly unbearable; I know to steer clear of big box stores. In combination with left hemispacialagnosia, where some stimuli arose from the incomprehensible left world, this was particularly distressing. When eating with friends, I found it necessary to sit where no one or other source of sensory stimulus was to my left; a task complicated by my not recognizing that there was a left to avoid. Well-meaning occupational & speech-language therapists attempted to assist me with exposure therapy to build tolerance, using real-world and virtual exposure to high-stimulus environments, but I needed baby steps; there are few environments short of an isolation tank or my sweet cabin in the Maine woods that are not overwhelming. I didn’t need created experiences for “exposure therapy;” it is difficult to avoid challenging situations, and the high-stimulus real-world and virtual environments prescribed were merely disorienting & exhausting. Craniosacral therapy and simple DIY use of a still-point device have helped somewhat, mostly with short-term benefit. The most dramatic intervention was my initial reiki session, sent distantly from Maine to Oregon; 3 months afterwards, my grandperson chose to have their birthday party at the Quarterworld arcade in Portland, Oregon; in addition to multiple arcade games on the floor, with their flashing graphics & blaring audio, there were several large wall-mounted widescreen monitors displaying visually rich audiovideo content; three months prior it would have been my personal hell; but I was able to enjoy Bug’s delight & the assembled company of friends & family. Afterwards, it was necessary to recover across the street at the Tao of Tea, where the collective pulse of the wait staff is 40, but I managed to survive the experience, & actually enjoy much of it.

Brainfog feels inseparable from the above, and from the impact of sleep disturbance. I was introduced to the term & concept from Claudia Osborn’s book Over My Head and from my participation in a brain injury day program some 2 years after my stroke, describing my inability to perceive the world crisply. I can’t help but think of Tom Hank’s “brain cloud” in Joe vs. the Volcano. In trying to describe it, it feels like one too many beers (which for me has always been one), or the feeling of 4pm following a busy call night in residency, or 9 a.m. following a transcontinental red-eye flight. I’m cautious around social contacts, and often feel the need to explain that I don’t use alcohol or other drugs; I can’t in fact tolerate the occasional beer or glass of wine; a bottle of wine used for risottos lasts me 6 months. I’ve never been a coffee drinker, but chocolate & oolong teas, my xanthines of choice, have minimal impact. Sugar makes it far worse, tho if accompanied by protein, as in ice cream, I can tolerate small amounts. In the brain injury program, the approach encouraged was to recognize & accept it, & to learn to negotiate life with brain fog as a new reality. Several years in, a new physiatrist recommended a trial of amantadine, which has been demonstrated to improve cognitive function in traumatic brain injury and in Long COVID; I tolerated it poorly, as I did many adventures in pharmacology, with systemic ‘flu-like symptoms, & despite some early improvement noted by my wife (which I however did not appreciate subjectively) I had to discontinue its use . I had some minimal transient success with homeopathic plumbum.

Sleep disturbance - It’s reported that 20 to 40 percent of stroke survivors experience sleep-wake cycle disorders, most commonly involving sleep-disordered breathing including central & obstructive sleep apnea. I’ve had 2 difficulties with sleep; fragmentation, with subjective wakings every 2-4 hours, and, more concerning, unrested waking, waking feeling as if I’ve had no sleep at all, even following a total of 10-12 hours sleep or the rare occasions of 8 hours of uninterrupted sleep. I can recall only one occasion of waking feeling rested from a night’s sleep in the past 11 years, as a random event for which I can offer no explanation. Feeling that sleep disturbance might underlie my persistent “brain fog,” I consulted a sleep specialist 2 years out from my stroke, located with the assistance of a friend with interest in sleep medicine. I underwent formal sleep study with polysomnography, wired with 12 leads recording electromyographic muscle activity, ECG, EEG, pO2, and chest & abdominal excursions. This is intended to detect sleep apnea, as well as restless leg syndrome & periodic limb movement disorder. The study revealed no apneic episodes, but suggested periodic limb movement disorder (not to be confused with restless leg syndrome). In retrospect, I strongly suspect this was an artifact of the study, which involved a highly atypical night’s sleep in a strange environment, with timing that did not match my normal sleep/wake cycle, and the need to slot my difficulties into one of 3 accepted diagnoses; subsequent self-monitoring over several months with a device that monitors breathing & gross body movement in my own bed did not record any unusual limb movement. I was started on gabapentin, and later on ropinirole; gabapentin may have had a minor effect on sleep fragmentation, but neither of these had any impact on the restorative quality of sleep, and both were poorly tolerated. I subsequently consulted 3 other sleep specialists, basically learning that the focus of the profession is sleep apnea, and was actually rejected by one practice on pre-screening of my medical record for not having the referral diagnosis of sleep apnea. Eventually I discovered a team working specifically with sleep disorders & brainfog in brain injury, and self-enrolled in a study investigating early morning bright light exposure and branched-chain amino acid supplementation on these. I saw some benefit on sleep fragmentation, but not on rested waking or brain fog, from early morning bright light exposure; but none from branched-chain amino acid supplementation, which I had to discontinue following the study due to expense. But in the course of this, met a physician involved in research on the glymphatic system, who speculated that my stroke may have impaired glymphatic circulation in its role of clearing metabolic waste, including adenosine, from my brain during sleep, suggesting I might discuss the use of prazosin with my family physician. Unfortunately, I did not qualify for her functional MRI studies of glymphatic function, which were VA sponsored and limited to Gulf War veterans with traumatic brain injury. Prazosin has been of some modest, tho respectable, benefit; I still wake feeling unrested, but less brain dead. In desperation, I’ve trialed some other medications to enhance normal sleep; the tricyclics nortriptyline, amitriptyline, and doxepin, which have had minimal effect, with discomforting adverse effects. I’ve of course explored homeopathic options, including Valeriana , Avena, & Scutellaria in potency & in drop doses of tincture, and mind/body interventions including progressive relaxation, imagery, & heart-rate variability biofeedback; and have a 55-year history of zen practice. Management of chronic pain, especially neck pain, helps to minimize the extent of night wakings. My current sleep regimen involves exercise early in the day (I live in one of the most beautiful parts of the world, adjacent to Acadia National Park, with walking trails out my cabin door, and have a rowing machine & bicycle on a stationary trainer for use in inclement weather), with early morning bright light exposure (my cabin’s porch, or an SAD light box) and limited evening screen time, with the Night Shift option enabled on my Mac, melatonin at bedtime (started in hospital at the time of my stroke as a neuroprotectant), and prazosin. The tin roof on my canin is lovely in a rainstorm, & I have a rainsounds APP on my phone I occasionally use at night, a barred owl outside my loft window who sings to me at night (I cook for myself, but she kindly asks), and peepers in the spring. If I’m consistent with this program, I sleep more soundly, with less fragmentation, but still wake consistently unrested.